Assumptional analysis and conflict modes

Ralph Kilmann

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Ian Mitroff and I developed a systematic methodology for uncovering – and then revising – the hidden assumptions behind decisions and actions. This same methodology can provide new ways of thinking about and then choosing the right conflict mode for a given situation.

I define assumptions as all the things that would have to be true in order to argue, most convincingly, that your beliefs are valid and that your actions will be effective. The beauty of “assumptional analysis” is first surfacing all the underlying, often unstated assumptions so you can find out if they are actually true, false, or uncertain. By seeing your assumptions face-to-face, you have the chance to revise them, which will surely inspire you to change your beliefs or modify your behaviour

Assumptional analysis begins by stating, either orally or in writing, your belief or intended behaviour: “Using the competing mode is the best way for me to resolve this conflict at this time.” You then write out what would have to be true about each aspect of the situation – the other person or persons, the culture of the organization, the reward system, and so forth – in order for you to argue that your choice of mode will be most effective for you and others, including the organization, both short term and long term.

In most cases, you will write out from 10 to 30 assumptions about all the people – both internal and external stakeholders – to support your behavioural intention. To give maximum support for the competing mode, for example, you would have to assume that the outcome of the conflict is more important to you than to others. You might also have to assume that the culture of the organization actively discourages people from taking the time to develop a more in-depth, win-win solution for all concerned. Moreover, to give maximum support for the competing mode, you would also have to assume that there wouldn’t be any unintended consequences from asserting your needs over other people’s needs in this organization.

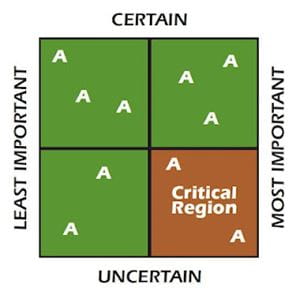

You then sort all your assumptions according to two distinctions:

- How important the assumption is to your behavioural intention (most important versus least important)

- Now that you recognize your assumption, how certain you are about whether it is true or false – or perhaps you have no idea (certain versus uncertain).

These distinctions result in four categories of assumptions:

- Most important and certain

- Most important and uncertain

- Least important and certain

- Least important and uncertain.

Not surprisingly, the primary focus for this analysis is on the most important assumptions that can negate your best intentions. In particular, any assumption (A) that falls into the Critical Region makes you most vulnerable to being dead wrong. If you are wrong about that assumption, you can no longer argue for the efficacy of your behavioural intention – and yet you have no idea if that assumption is actually true or false!

By seeing which assumptions are most important and false, however, you can easily revise them without further discussion or investigation. Often, it’s startling to discover that you were about to use a conflict mode that was solidly based on an assumption you already knew to be false!

By seeing which assumptions are most important and uncertain – since these assumptions are just as likely to be either true or false – you can now spend some time to investigate the truth or falsity of these assumptions through further discussion or research and then revise them, based on what you learn. For example, if I must assume that my needs are more important than yours, how do I know that? Maybe I need to ask you outright, rather than make blind assumptions that will surely undermine my approach to conflict management.

Bottom line: We are always making all kinds of unstated, untested assumptions about the other people in a conflict situation, including the attributes of the organization itself. By being more aware of our assumptions, however, we can significantly improve our success in choosing the right modes and then resolving our conflicts. But since it takes time to do assumptional analysis, we should use this method only when the conflict is very important to resolve and we, in fact, are right about this assumption!

For more information about assumptional analysis, see my article on problem management at www.kilmanndiagnostics.com/problem.html.

Ralph H. Kilmann, PhD, is CEO and Senior Consultant at Kilmann Diagnostics in Newport Coast, California. Formerly, he was the George H. Love Professor of Organization and Management at the Katz School of Business, University of Pittsburgh – which was his professional home for 30 years. He earned both his BS degree and MS degree in industrial administration from Carnegie Mellon University (1970) and a PhD degree in management from the University of California, Los Angeles (1972). Kilmann is co-author of the TKI assessment and has published more than twenty books and one hundred articles on conflict management, problem management, organizational design, change management, and quantum organizations.