Should I stay or should I go? David Cameron’s negotiation style with the EU

Rob Bailey

David Cameron’s veto at the recent EU summit has given us all something to talk about. At OPP, the whole episode has been a reminder of the variety of ways that a person might approach conflict and negotiation.

From reports of Cameron’s approach, it appears that he saved up his demands until late in the negotiations, then, as his stipulations were rejected, he withdrew his support and used his veto. As a result, he’s been accused of being a poor negotiator by some and as a decisive leader by others. How would a psychologist describe his approach? Here’s my take…

For the purposes of this blog, I use ‘conflict’ to mean a situation where two opposing positions appear to be difficult to satisfy.

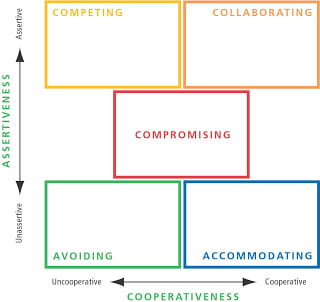

I will use the Thomas-Kilmann model of conflict handling modes, as it usefully divides the possible conflict approaches into five:

Each style has a different motivation for you and for the other party. Your actions can be targeted at getting what you want (assertive), and/or trying to satisfy the needs of the other (cooperative). For example, if you try to meet your needs and the needs of another, your style is likely to be collaborative; if you are trying to simply meet your own needs, your style is competitive.

Although some of these might look more desirable than others, each has its own contribution to make and a skilful negotiator will apply the right one at the right time:

- Collaborating aims to satisfy both parties, but can require time and a full exploration of not only the position that someone is putting forward, but also their concerns behind that position

- Compromising might end up with both parties only getting a little of what they really wanted, but might be quicker and more suitable than collaborating

- Competing might be necessary for quick decisions

- Accommodating gains goodwill, but might lose some respect if over-used

- Avoiding saves time on things that can be postponed, but will rarely solve big issues.

From what is publically known about the negotiations at the EU summit, it appears Cameron took a competitive, rather than a collaborative stance. To build alliances and collaborate with others, you need to find the time to mutually air positions and concerns. It appears that Cameron aired his concerns very late – so late that many EU politicians say there was not the time to deal with his demands. Unless he made some error of judgement, it appears that he set out meaning take a competitive stance and had very little interest in ever finding a collaborative solution.

As for others involved, they also appeared to show different conflict handling styles:

On Cameron’s return, Nick Clegg failed to appear at the Prime Minister’s side, so appeared to have adopted an avoiding style.

Ed Miliband, as you would expect, immediately took a competitive stance in his public statements, as did Alex Salmond. However, when questioned, Salmond suggested that he would have started discussions much earlier to make sure that negotiations were settled by consensus. This appears to be suggestive of collaboration and/or compromise.

Although these statements and behaviours may be posturing, they show examples of four out of the five conflict styles (there’s little evidence of accommodating).

Back to Cameron, it appears that this is not the first time he’s tried saving things up until the last moment; he reportedly employs a ‘full bladder’ technique to make sure he has an appropriate level of tension during speeches or negotiations.

Fortunately there’s some award-winning research into this topic. Lewis et al (2010) won an Ig Noble award for showing that as bladder-tension increases, working memory and attention decreases.

EU negotiations are a complex issue, so it may be years before we know what the right choice would have been. However, bladder control is straightforward. When you need to, you should go.