Do learning strategies mediate the relationship between personality and stress?

Gaby Walker, Support R&D Consultant at OPP

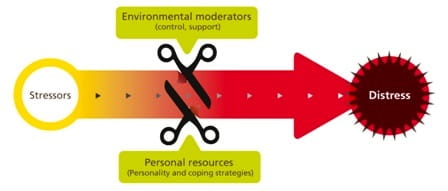

We have all felt stress at work at some point in our lives. It has been estimated that over 105 million working days are lost each year because of work-related stress, and OPP’s own research found that over 70% of UK workers find their work stressful. However, whilst low-level stress affects most people, this doesn’t have to lead to distress for any one individual. Using the right coping strategies can cut the link between stress and distress. Manageable amounts of pressure can then have a positive impact and enhance motivation and increase engagement.

We have all felt stress at work at some point in our lives. It has been estimated that over 105 million working days are lost each year because of work-related stress, and OPP’s own research found that over 70% of UK workers find their work stressful. However, whilst low-level stress affects most people, this doesn’t have to lead to distress for any one individual. Using the right coping strategies can cut the link between stress and distress. Manageable amounts of pressure can then have a positive impact and enhance motivation and increase engagement.

For those of us in the world of work, it is easy to forget that all of this applies to students too. With this in mind, OPP’s research team looked at how a particular coping strategy, individual ‘learning styles’ and personality traits together affected university students’ perceptions of how stressed they were. Before going into the details of this research, however, it is worth looking at personality and coping strategies in a little more detail.

The way in which we react to stress also depends on our personalities. For example, OPP’s own research shows that an individual’s level of Anxiety predicts their overall reaction to stress, and that people who are more Emotionally Stable feel less stressed and are less affected by individual stressors.

What’s more, the links between personality and stress may be affected by the ways in which we learn. As individuals, we adopt learning behaviours based on our personalities – but some learning behaviours are found to be more effective than others. For example, you are less likely to experience high levels of distress if you have a tendency to apply previous knowledge to new situations in order to solve problems (Critical Thinking). You are also less stress-prone if you plan, monitor and regulate your learning activities (Self-Regulation). However, if you tend to learn by rote (Rehearsal), this can induce stress, and has even been linked to poor academic performance. Research has shown that extraverts more often adopt help-seeking behaviour, peer learning and critical thinking, whilst people with higher neuroticism scores tend to be poorer at critical thinking.

So what does this all mean? Well, if effective learning strategies minimise levels of stress, this has many implications for developing techniques to manage stress. With this in mind, our research team led an investigation into the effect of critical thinking and self-regulation on the relationship between personality traits and perceived stress among university students.

Not surprisingly, personality was found to be the biggest predictor of stress. Individuals with high levels of anxiety are more likely to feel the pressures of work and stress. Additionally, people who work more independently, as well as those who do not share or vocalise their problems, will also experience higher levels of distress.

Our personalities were also found to predict our learning styles – but not to the same extent as they predict stress. For example, people who can maintain an emotional balance when under pressure are more likely to adopt a planned approach to learning. Those who are usually very physically tense will find it difficult to apply previous knowledge to new situations in order to solve problems. However, even though personality is a powerful predictor of perceived stress, and of our likely learning style, we can still choose to adopt more effective learning styles and coping strategies. This will reduce the negative impact of this stress, whatever your personality make-up.

These findings have important implications for people who want to manage their stress and achieve better performance in the work environment. This is especially important in today’s competitive job market, as well as for a person’s own well-being.

Universities and workplaces should focus on the importance of support services, social support and stress management programmes to help employees and students deal with personal problems that might adversely impact their work performance, health and well-being. These services can include counselling, employee assistance programmes, networking opportunities and stress management initiatives. Individual, team or management development also help to create a resilient environment.

Crucially, this development can address wider organisational issues head on, such as communication, conflict, decision-making and leadership. Such interventions are instrumental in preventing additional stressors from causing distress – making a pretty strong case not just for direct stress management, but also for an overarching development strategy that meets the needs both of individuals and the organisations in which they thrive.