Polarity management and the MBTI

Betsy Kendall, COO and Head of Professional Services, OPP

Over the last 15 years many organisations seeking to develop leaders have embraced strengths-based approaches. The wholehearted enthusiasm with which these have been adopted is partly a backlash against decades of using “deficit approaches”: the mantra that leaders will only succeed if they are aware of their weaknesses and work diligently to fix them. What developers came to realise is that focusing on weaknesses alone, without acknowledging the power of strengths, is demoralising and may even backfire and lead to failure.

Strengths based approaches came to the fore with Gallup’s Now, Discover your Strengths. The core of this view is that battling to transform weaknesses takes more time and energy than it’s worth, so better to put our energy into embracing and capitalising on our natural gifts: no more hammering square pegs into round holes. The problem is that focusing on strengths alone may be ultimately Pollyanna-ish, self indulgent and in denial of the reality that some skills are required regardless of whether they come naturally.

Both approaches have clear upsides and potential downsides. Neither approach alone has it all; so which should developers adopt?

Dr Barry Johnson’s model of polarity management can be used to address the conundrum. He defines polarities as ongoing issues where there is no single right answer and where there is a tendency to swing from one polar solution to its opposite. An organisational example of a polarity is whether it is better to be centralised or decentralised. Both have upsides and downsides. Johnson contends that, rather than attempting to solve the unsolvable, we should strive for the best of both worlds. We do this by recognising the polarity and actively managing it.

There is a parallel here with psychological type. When people are introduced to the MBTI®, the focus is on their strengths – finding what comes naturally and using knowledge of preferences to achieve greater engagement and greater achievement. This makes the MBTI process one of the most constructive, validating and memorable there is. It is my experience that for people with preferences relatively rare in their work environment, the MBTI process may be the first time they have felt okay about acting naturally, and realising that their inherent gifts make an important contribution even if their style is different from their colleagues. At the same time, some criticise the MBTI for being too positive – “seeing the world through rose-tinted spectacles.”

If this focus on using likely natural gifts is the only message people get about type, it can lead them to indulge their preferences, overusing strengths to the point where these overshadow everything else. There is a danger that people make excuses for not flexing when faced with situations that legitimately require them to use their non-preference.

Jung’s theory of type was never about the use of one preference to the exclusion of another – it is a theory of one preference and the other. If a person hasn’t fully accessed and used the strengths linked to their type preferences, focusing on these natural strengths will probably be the best way for them to start their development journey. On the other hand if the person has been deploying their preference-based strengths for a long time, there may be more mileage in focusing on the other polarity, ie developing aspects of their non preferences that they really need to master if they are to avoid plateauing or derailing.

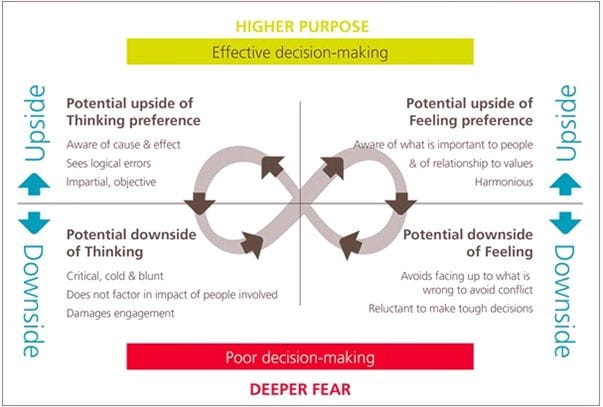

The diagram below is based on Johnson’s “Polarity Management Map”.

The trick is to consciously operate mostly in the top half of the matrix, minimising time spent in the downside areas. A well-managed polarity is one in which you capitalise on the inherent tensions between the two poles – for instance, between Thinking and Feeling, leveraging the synergies between the opposites. If you do this you will achieve more of your “higher purpose”. A polarity is poorly managed if you focus on one pole to the exclusion of the other, falling into the trap of thinking your preference is ‘right’ and that the opposite preference is ‘wrong’. For example, if you have an INtuitive preference you may think Sensing risks getting mired in detail and leading to faulty decision making; or if you have a Thinking preference and may think Feeling is soft and subjective, and that to listen to that perspective will end up in faulty decision making. Although this is a distortion of what psychological type is about, I suspect a number of us still harbour such biases.

Where you only operate on the left or right of the diagram, you will very likely display all the upsides and then all the downsides of that one preference in your decision making: your deeper fear is more likely to come true. To get out of this rut you must first recognise that there is a polarity to be managed. You need to work to understand the benefits and value of the opposite preference, also acknowledging the downsides of each preference pole. Ask (for example) “how can we get the benefits of Feeling whilst holding on to the benefits of Thinking in order to make the most effective decisions?”

There will be a learning curve, particularly for those who (in this example) haven’t actively accessed Feeling much in the past. It will probably feel awkward to begin with as they start to use Feeling, and they may dip into the downside of that function for a while before the upside benefits become solidly apparent. The eventual benefits, however, are potentially job-saving and life-enhancing.

Polarity management recognises that each pole represents just half the story. The MBTI process navigates the space between the poles, satisfying both the desire to build strengths and the need for hard-hitting development of out-of-preference areas.