Decisions, self-confidence and the glass ceiling: can the MBTI framework help?

John Hackston, Head of Thought Leadership, OPP

Women form half of the UK population, yet make up less than 10% of executive directorships in FTSE 100 companies. Plain old-fashioned sexism could be part of the reason for this, but other factors have been suggested, including differences between the sexes in decision-making style and in self-confidence. Here at OPP, we thought we would try to shed some light on these issues.

First, we looked at data from over 600,000 people who had completed the MBTI questionnaire online. We did find, as we unfortunately expected, that women were significantly under-represented at higher levels in organisations, and over-represented at lower levels. Those at the top level were 2.5 times more likely to be men than women; those at ‘employee’ level were 1.5 times more likely to be women than men.

One of the dimensions of the MBTI instrument, Thinking–Feeling, is about the way in which you tend to make decisions – do you prefer to make decisions in an objective logical way, on the basis of impersonal criteria (Thinking), or do you prefer to take a more values-driven approach, taking individual personal circumstances into account (Feeling)?

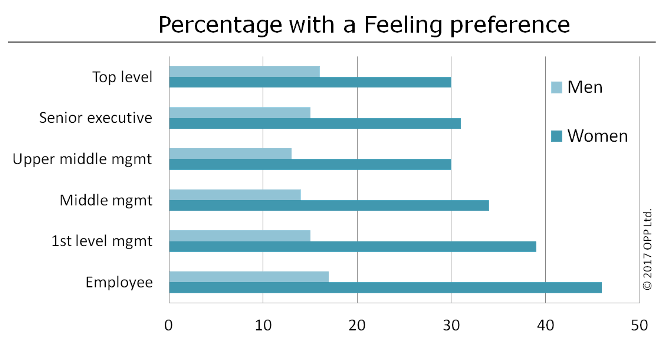

In line with other research, we found that women were significantly more likely than men to prefer the values-driven Feeling approach.

It was in the interaction between occupational level, gender and decision-making style that the results really caught our eye, however. For men, the proportion of people with a Feeling preference did not vary much between levels. For women, the higher the occupational level, the lower the proportion of those with a Feeling preference. The percentage varied from 46% at employee level down to just 30% at top level. This suggests that for women, it may be more difficult to be promoted if you have a Feeling preference, but for men it doesn’t matter – all things being equal, you are just more likely to reach a higher level.

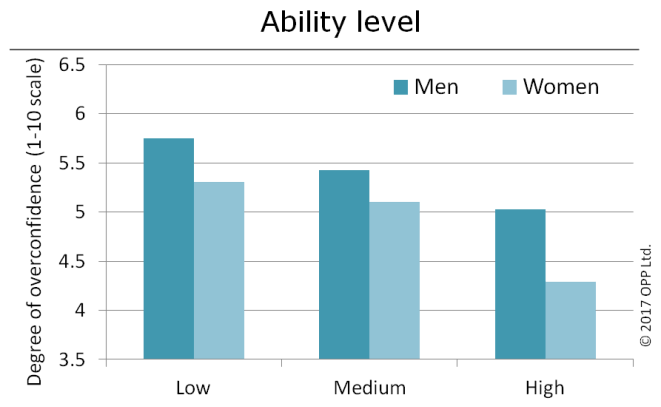

In a separate study, we looked at how confident people were about their answers to an ability test. There was no actual gender difference in ability, but men were more confident they had answered correctly – and more overconfident when they got things wrong. In fact, for any level of ability, women were on average less confident in their ability and (compared to the test results) less overconfident than men.

In general, people with a lower ability level were more likely to overestimate their performance – a phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. Overall, the group most likely to overestimate their abilities were less able men; the group most likely to downplay their skills were the highest-scoring women.

So it seems that women are more likely than men to use values-based decision-making, and there is evidence that this can make for a very effective leadership style. However, organisations may see this approach as less valuable, and this might contribute to fewer women being promoted to higher levels. Women are on average less confident of their abilities than men, and this is likely to make the situation worse still.

But it’s not necessarily all doom and gloom. Those of us working with organisations have a role to play in helping our clients to see why the values-based approach to decision-making can be useful and valid. Instruments like the MBTI assessment, which promote diversity and an understanding of others, can be effective here.

OPP presented this research at the British Psychological Society Division of Occupational Psychology conference on Wednesday 4th January and will also present the results in a webcast on 2nd February – sign up now.